Why Hollywood Is Not Enough to Beat China's Economic Power

Dan Wang's framework exposes how China's engineering state challenges Western beliefs that Hollywood, finance, and services can sustain global power over manufacturing prowess.

Almost by chance, while browsing YouTube, we came across a series of interviews with Dan Wang, research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover History Lab. In August 2025, Wang published BREAKNECK: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, a book already longlisted for the Financial Times Business Book of the Year and widely discussed in American media.

What makes Wang’s perspective stand out is the mix of experiences that shaped it. Born in China, raised in Canada, and having spent nearly a decade living in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai, he has observed China’s technological rise from the inside. Through his annual letters, essays in Foreign Affairs and The Atlantic, and frequent podcast appearances, Wang has built a reputation for clear, often counter-intuitive analysis—neither celebratory nor dismissive, but attentive to both strengths and contradictions.

At the core of his thinking is a provocative distinction: China as an “engineering state” versus the United States as a “lawyerly society.” This framework, which challenges conventional wisdom, frames his broader vision of a decades-long contest between two very different powers. His arguments, especially in interviews, reveal not only China’s ambitions but also its internal tensions and global implications—an invitation to rethink how we understand economic and geopolitical strength today.

The 21st century has witnessed China's undeniable economic ascendancy, a phenomenon that has fundamentally reshaped global geopolitics and exposed a critical delusion in Western strategic thinking. While China's economy ranks as the world's largest by some metrics and second by nominal GDP, with forecasts suggesting it could account for approximately 45% of global manufacturing output by 2030, the West continues to cling to the belief that service-based economies built on entertainment, finance, and information can maintain dominance over nations that actually build things.

This misconception, rooted in decades of deindustrialization and overconfidence in "soft power," is now colliding with the harsh realities of geopolitical competition. His insights reveal how fundamentally different approaches to power and development are reshaping the global order, with implications that extend far beyond economics to touch the very foundations of national strength.

The Engineering State Versus the Lawyerly Society

China's transformation into a manufacturing superpower wasn't accidental—it resulted from deliberate strategic choices made by leaders who understood that physical capabilities form the foundation of all other forms of power. The shift began with Deng Xiaoping's conscious decision to elevate engineers to the highest levels of government, a corrective measure against what Wang describes as the "mayhem of the Mao years," characterized by romantic, poet-like leadership that inflicted "strange disasters" on the population.

Deng's vision of a "highly efficient technocracy" led to engineers dominating China's political hierarchy. By 2002, all nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee held engineering degrees. This wasn't a mere coincidence—it reflected a fundamental belief that nations advance through concrete achievements rather than abstract theories. The engineering mindset translates into what Wang describes as the conviction that "a mega project is kind of the answer to any number of quandaries," leading China to "build its way out of all of its problems" with an endless supply of bridges, roads, highways, and industrial plants.

Wang's personal experiences illuminate this difference starkly. Living in Shanghai, China's richest city, he found a place "full of ease and full of beauty," with an ever-expanding subway system and a city government committed to doubling its parks by 2025. He described Shanghai as "much more functional than New York City." The contrast became even more pronounced during a bike ride through Guizhou, China's fourth-poorest province, where, despite having a GDP per capita comparable to Botswana, he encountered "much better levels of infrastructure than one could find in much wealthier places in the United States like New York State or California." Guizhou boasted "11 airports, 50 of the highest bridges in the world and brand new spiffing highways"—demonstrating that, as Wang concludes, "China builds and the US doesn't."

The American predicament stems from what Wang identifies as its "lawyerly society." From the founding fathers—many of whom were lawyers—to the modern Democratic Party, which consistently nominates law school graduates for presidential roles, the United States remains deeply entrenched in a legalistic culture. While this helps America avoid "stupid ideas like the one child policy," it also results in a country that is "really good at stopping a lot of things" and therefore "doesn't have functional infrastructure almost anywhere." The high cost of infrastructure projects in Anglo countries, often due to common law systems empowering individuals to block developments over "specious concerns" like noise pollution or garden shade, further exacerbates this dysfunction.

The Mirage of Post-Industrial Power

For decades, Western policymakers and economists promoted the idea that advanced economies naturally evolve beyond manufacturing into service sectors. Hollywood, Silicon Valley, Wall Street, and other knowledge-intensive industries were celebrated as the pinnacle of economic development. This narrative suggested that while other nations might handle the "dirty work" of production, the real value—and therefore real power—lay in design, finance, and cultural influence.

This perspective seemed vindicated by America's cultural dominance. Hollywood movies played in theaters from Beijing to Berlin. American brands became global symbols. The dollar remained the world's reserve currency. Manufacturing jobs were shipped overseas in pursuit of cheaper labor costs, a trend celebrated as economic efficiency rather than strategic vulnerability. The belief that a service-heavy economy reliant on "Hollywood, Silicon Valley, Wall Street, healthcare, and consulting" could sustain great power status became conventional wisdom.

Yet this entire edifice rested on a dangerous assumption: that control over ideas, entertainment, and financial instruments could substitute for control over physical production. The COVID-19 pandemic shattered this illusion when the United States, despite its technological prowess, struggled to produce basic necessities like cotton swabs and masks. American manufacturers faced severe challenges while the defense industrial base struggled to rebuild munitions stockpiles and deliver naval ships on schedule.

The outsourcing of manufacturing since the 1990s wasn't a "deliberate choice" by the US government but rather a "process of business lobbying" seeking cheaper production costs. Meanwhile, the Communist Party consciously welcomed major American manufacturers like Apple and Tesla to China, using them strategically to train Chinese workers and rapidly advance toward the global technological frontier.

China's Quest for Technological Mastery

China's strategic objectives extend far beyond mere economic growth—they encompass achieving technological mastery and strategic autonomy to secure the nation's position in competitive global markets. This ambition is embodied in plans like "Made in China 2025," which Wang describes as a "grand ambitious plan" targeting dominance in future industries, including electric vehicles, industrial robotics, clean technologies, maritime technologies, and agricultural equipment, often with "exquisite percentages" detailing desired global market shares.

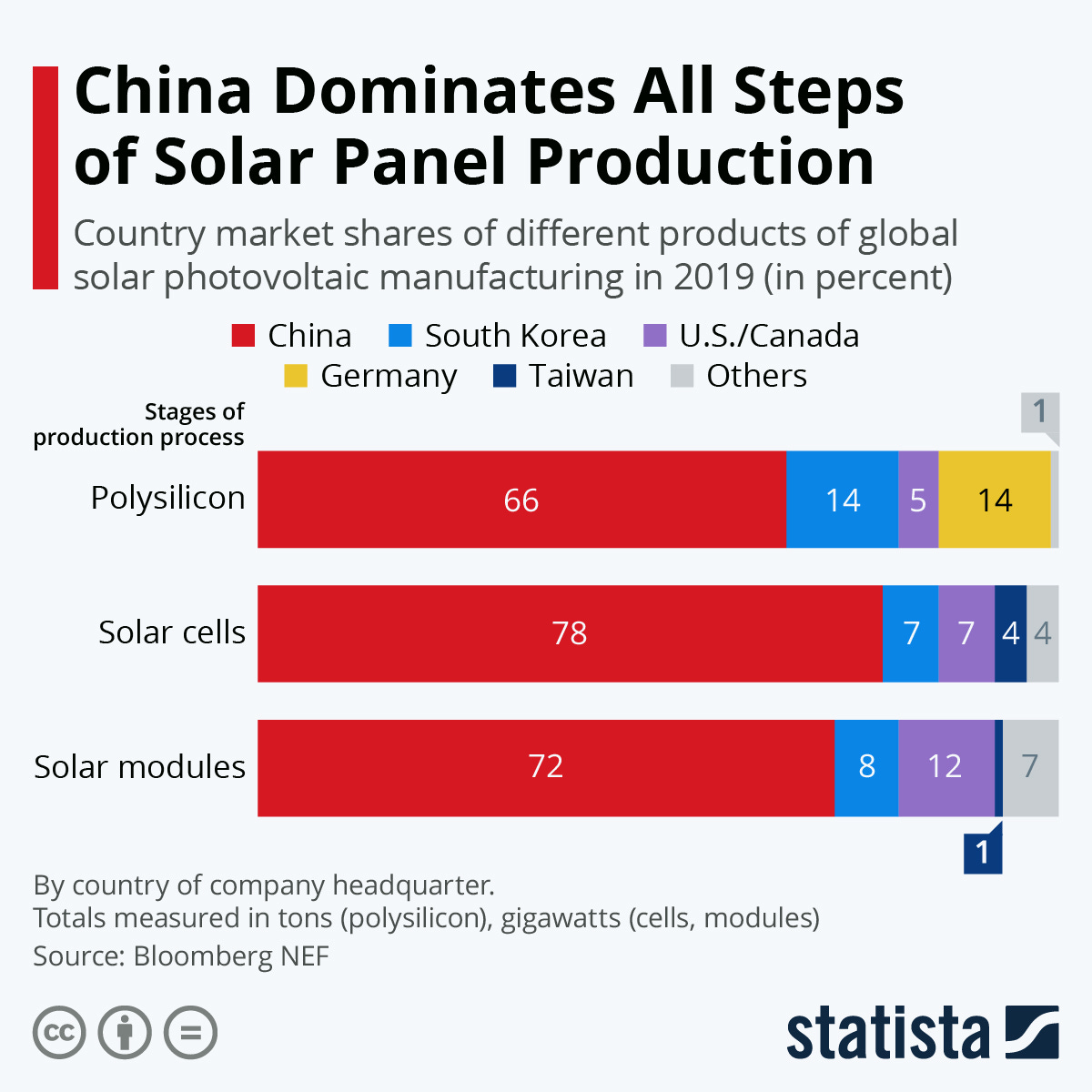

The results speak for themselves. China has demonstrably succeeded, becoming a leader in electric vehicles and industrial robotics while maintaining what Wang calls a "complete chokehold" on the solar industry (90% ownership) and rare earth magnet processing (90%). Under Xi Jinping, China's leadership treats its economy "as if it were a vast hydraulic system made up of a series of valves," employing "social engineering" approaches that have seen the Communist Party "re-engineer" entire sectors.

This strategic reengineering was dramatically illustrated by China's crackdown on online tech and property companies from 2020 to 2022, which wiped out a trillion dollars from China's stock market but served a crucial purpose: funneling China's "best and brightest" from consumer tech, cryptocurrencies, and hedge funds into industries "more critical to strategic needs," such as semiconductors, aviation, and chemistry. As Wang notes, while this creates "miserable competition" and "miserable returns for investors," it demonstrates that "the state wins, consumers win, but it is actually pretty rough for any of these companies"—socialism with Chinese characteristics in action.

A key driver behind China's technological push is energy independence. Recognizing its vulnerability to Middle East oil and Russian gas dependence, China is heavily investing in domestic renewable energy sources including solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, alongside nuclear energy and hydrogen economy experiments. This ensures "energy sovereignty," meaning China prefers its population to drive electric vehicles powered by domestic coal, solar, and wind rather than imported fuels—a strategy rooted in what Wang identifies as a "civilizational centrality" belief echoing the Qing dynasty's Emperor Qianlong, who famously told the British, "We have no need of your trinkets."

The Power of Process Knowledge

Central to China's technological advantage is what Wang calls "process knowledge"—tacit knowledge or industrial expertise that cannot be easily transferred through blueprints or patents. He likens it to cooking: simply having the best kitchen and most detailed recipe doesn't guarantee success without the experience and intuitive understanding that comes through practice. The West, particularly the Anglosphere, has tended to view technology as blueprints, patents, and physical objects, forgetting that much manufacturing success depends on apprenticeship and knowledge transferred through hands-on experience.

China excels at "climbing these ladders" of manufacturing complexity, starting with simple textiles and progressing to sophisticated consumer electronics like iPhones and drones. The transformation of Shenzhen from a textile backwater to the production hub for iPhones illustrates this progression. Wang draws an evocative parallel with Japan's Ise Jingu shrine, where craftspeople completely rebuild a wooden temple every 20 years, teaching the next generation complex joinery techniques in the process. This continuous renewal ensures preservation of "wood technology" through active practice—an ethos of continually investing energy and practice into industrial knowledge that Wang argues the West has lost.

While the West focused on what Wang calls "sounding clever industries" like television, journalism, and finance, China built its physical manufacturing prowess. The crucial insight is that simply stealing blueprints, as China is often accused of doing, doesn't impart the experiential "process knowledge" needed to recreate complex products like Rolls-Royce jet engines or advanced semiconductors. This immense investment in skilled workforces and active cultivation of industrial expertise forms the basis of China's technological leadership.

China's success in solar power exemplifies this approach. While Bell Labs made the original scientific discovery in 1954, it remained largely a laboratory curiosity. Germans developed it into a larger industry in the 2000s, but Chinese firms "copied the German expertise and completely overran the industry." As Wang explains, the Chinese are "better at climbing these ladders," not necessarily through pure invention, but by "building step by step, trying to perfect an industry in such a way that it becomes a completely new industry by the time it has been truly perfected."

The Limits of Soft Power

Hollywood's global reach remains impressive, but its influence proves surprisingly shallow when confronted with economic realities. Chinese audiences may watch American movies, but they drive Chinese-made electric vehicles powered by Chinese-manufactured solar panels. Cultural products can shape preferences and values, but they cannot substitute for the ability to meet basic human needs or provide essential infrastructure.

The fundamental problem with service-based economies is their parasitic relationship to underlying production. Finance requires something real to financialize. Entertainment needs physical infrastructure for distribution. Even the most sophisticated software runs on hardware manufactured somewhere in the physical world. When that production capacity migrates elsewhere, the entire superstructure becomes vulnerable.

Wang expresses deep skepticism about services' ability to "absorb even more of the US workforce," particularly as artificial intelligence eliminates entry-level positions in knowledge-based sectors. The assumption that everyone can become a software engineer, financial analyst, or media professional ignores basic mathematical realities about labor market capacity. Moreover, many service jobs depend on underlying prosperity generated by productive activities—restaurants, entertainment venues, and consulting firms thrive when there's disposable income to support them, but if that income stems from manufacturing wages, deindustrialization undermines the entire service economy.

Geopolitical Tensions and Strategic Mistakes

The US-China tech war exemplifies both the external conflicts China faces and the unintended consequences of Western policy responses. The Trump administration's 2018 initiative to blacklist numerous Chinese technology companies, particularly those in semiconductors, initially proved "very effective" in hobbling firms like ZTE and Huawei, which struggled without access to American technologies where the US held near-monopolistic control.

However, Wang argues these sanctions ultimately spurred China's technological self-sufficiency rather than containing its rise. By depriving companies like Huawei of American components, the US government "drove China's most technologically capable companies into the arms of the communist party," compelling them to build domestic ecosystems. Wang considers this a "strategic mistake," noting that the US would be in a "better place if Huawei were still much more dependent on American technologies right now than for it to be much more technologically self-sufficient."

This dynamic reveals a crucial asymmetry in the competition. Sanctions work best when targets lack alternative suppliers or domestic development capacity. But China's manufacturing ecosystem provides exactly those capabilities. When denied access to American semiconductors, Chinese companies didn't simply accept defeat—they mobilized their engineering resources to develop alternatives, reducing China's dependence on Western technology, which had been a long-standing goal of some Communist Party factions.

Internal Contradictions and Social Engineering Failures

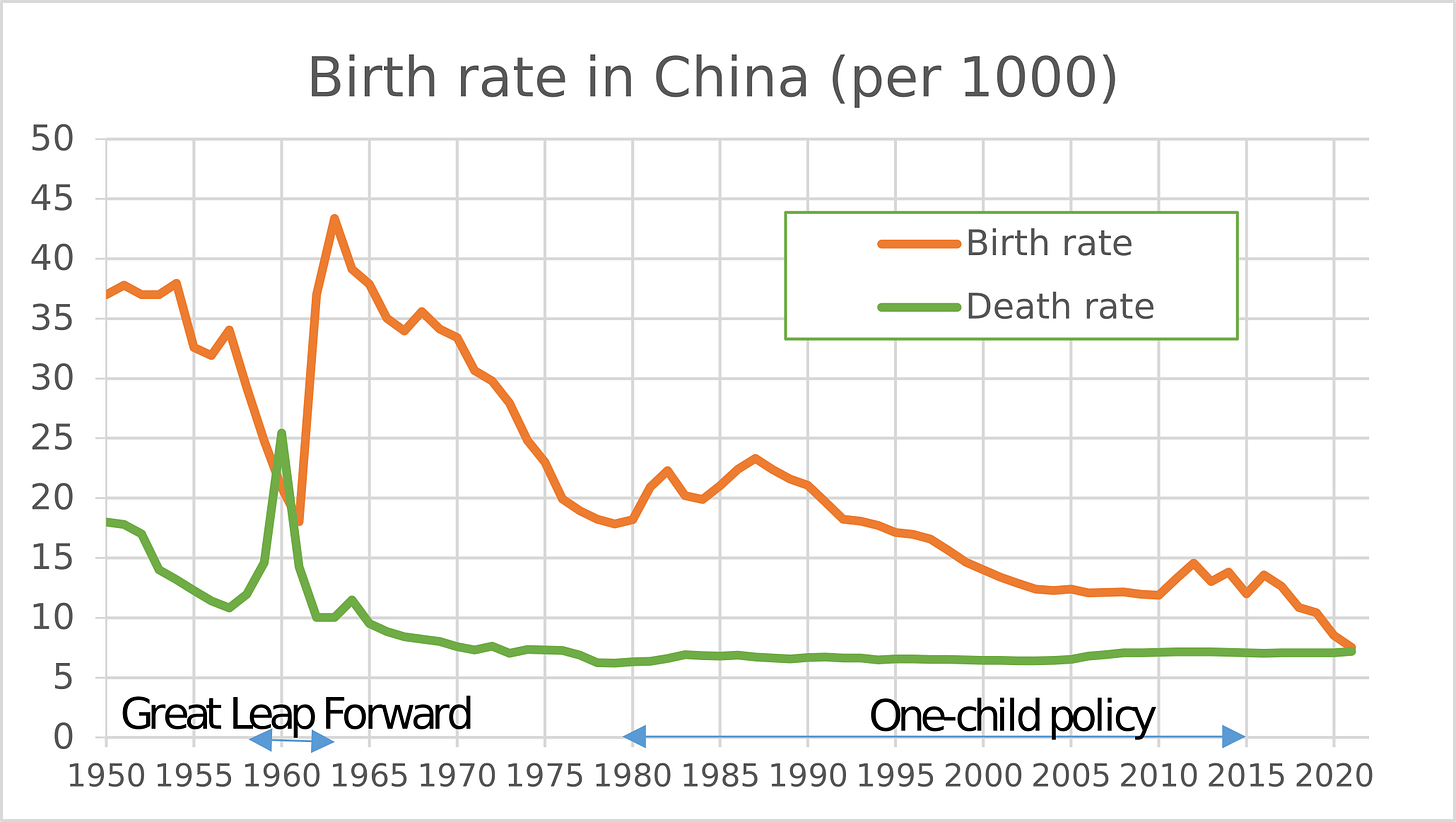

Despite China's impressive manufacturing achievements, its engineering approach produces devastating outcomes when applied to social policy. The most glaring example is the One-Child Policy, what Wang describes as a "radical experiment in social engineering" implemented from 1980 by leaders like Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun, heavily influenced by missile scientist Song Jian. Song applied mathematical models of missile trajectories to population control, creating a policy that sounded "quite scientific" but was enforced through "the most brutal means of forced sterilizations, forced abortions"—what Wang calls a "campaign of rural terror against overwhelmingly female bodies."

In 1983 alone, 16 million women were sterilized and 14 million abortions were carried out. The long-term impact is a rapidly aging population and plummeting birth rates that the government now struggles desperately to reverse. The Zero-COVID Policy of 2020-2022 represented another instance of extreme social engineering. While initially praised for controlling the virus through centralized quarantines and border closures, the later Omicron wave saw Shanghai—a cosmopolitan city of 25 million—endure what Wang calls the "greatest lockdown ever attempted in the history of humanity" for 8 to 10 weeks, leading to widespread food insecurity and "enormous distress" among urbanites.

These heavy-handed interventions have fueled significant brain drain and distrust within China. Wang notes that wealthy Chinese, entrepreneurs, and creative professionals actively seek to leave for places like Irvine, California, Singapore, or Japan, where "the state leaves you alone." Senior Communist Party members often send their children abroad, unsure if they themselves might be purged. Creative professionals face censorship, and after repeated instances, many "get quite mad and they move to a place like New York." Even lower-skilled migrants undertake perilous journeys, like crossing the Darién Gap to reach the US-Mexico border, seeking escape from a regime that can unpredictably "change its engineering plan tomorrow and strip your wealth away."

The Real Competition Ahead

Wang unequivocally states that both the US and China are "giant countries that are increasingly locking horns," and they are "not going to fall into the sea and just sink into the Pacific Ocean." He dismisses notions of either power imploding like the Soviet Union, asserting that the competition is "long-lasting" and will span "decades." This prolonged contest will be determined not by cultural influence or financial engineering, but by which system can deliver better material outcomes for its people.

"It’s not about the democracy. Part of why I wrote this book was to get us beyond these 19th century political science terms. I’m really allergic to political science terms like Democratic or capitalist, socialist, autocratic. Let’s try to be fun and inventive in having a new framework to think about these two big countries."

Manufacturing prowess has become the new geopolitical battleground. China's physical strength in manufacturing makes it a "manufacturing superpower," while America's deindustrialization could have severe consequences beyond economic decline. Wang warns that if the US "can't get its act together to produce drones and ships and munitions," it could face scenarios where it loses conflicts, particularly concerning Taiwan. The idea that a service-heavy economy can sustain great power status is met with deep skepticism, especially as AI development further limits entry-level opportunities in service sectors.

Regarding China's ultimate global ambitions, Wang suggests Beijing desires to be a "serene empire" that primarily dominates East Asian neighbors like the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia, rather than seeking wholesale replacement of US global hegemony across all domains. China's progress is "mostly constrained in the physical manufacturing world," suggesting regional rather than truly global hegemonic ambitions in the immediate future. The cultural soft power of the West, exemplified by Hollywood, is not the currency China seeks to compete with directly—its focus remains on tangible, material power.

The Foundation of Future Power

The true measure of a triumphant power will be its ability to "deliver well for its people"—providing functional cities, affordability, and clear economic futures. This requires mastering what Wang calls the "secure transport of light"—whether through fiber optic cables or semiconductors—the crucial physical infrastructure underpinning modern civilization.

Wang's analysis reveals that the contest between China and the West isn't fundamentally about ideology or values—it's about which system can provide tangible capabilities that improve people's lives. China's internal contradictions remain significant vulnerabilities: its effective Leninist technocracy driving modernization, clashes with socially engineered horrors, and widespread distrust among its populace. The "propensity of discontented Chinese to seek means of escape" abroad remains a potent American advantage, highlighting the enduring appeal of individual freedom even amid America's infrastructural and political challenges.

However, these advantages cannot compensate for the loss of manufacturing strength. The allure of Hollywood, while a powerful cultural force, cannot substitute for declining industrial bases or eroding manufacturing expertise. As China's rise demonstrates, the future global order will be shaped less by cinematic narratives and more by the cold, hard realities of who can build, produce, and innovate on a foundational level.

In this protracted, multi-faceted competition, military strength, technological prowess, and economic vitality are inextricably linked. Without mastery over tangible foundations—the ability to manufacture essential goods, build infrastructure, and maintain technological capabilities—no amount of cultural influence or financial sophistication will be sufficient to maintain global leadership. The competition ahead will test which approach to power and development can sustain itself over the long term, and history suggests that societies capable of producing what they need tend to outlast those that merely consume what others make.

Wang’s insights raise tough but important questions—not just about China’s future, but also about how the West chooses to position itself in this long-term competition. These aren’t issues that can be reduced to slogans or simple takes, but ones that deserve real debate and reflection.

That’s why we’re considering going a step further: trying to bring Dan Wang himself on our channel for an interview. If that’s something you’d like to see, let us know in the comments. Even better—tell us what questions you’d want us to ask him. Your input could help shape a conversation worth having.

Frankly, Wang doesn't appear to have a single original idea. Pointing out that China is led by engineers the US by lawyers, is old hat.

Wang's claim that during the "one child policy" millions were sterilised, etc., is pure American propaganda.

Further, there's nothing new about his claims re Covid. American propagandists have been rehearsing these claims for half a decade. However, I was living in Beijing when COVID hit and most people understood and accepted the necessity of the lockdowns. When a few years later a new outbreak hit Shanghai resulting in a prolonged lockdown, people protested, the government reviewed their policy and lifted most of the restrictions. The fact is, because of the lockdown, less than 6 thousand people died in China. That's proof enough of the correctness of the policy.

Wang claims he wants to go beyond 19th century labels. Yet, several times when referring to China, he uses the label Communist. Yet, when talking about America, I don't recall him once using the term Capitalist.

Could say more, but you get the idea.

Very interesting, mostly true, but there is a bit of silliness there.

The One Child policy was not stupid, it was essential to stabilise the population which has been achieved. Just look at the state of India and the Philippines where growth is out of control.

The idea that the Chinese are angry with their government is easily disproven by looking at Pew and others which find world topping satisfaction ratings of over 90%.

But as for the unsatisfied minority, they don't have to find "means of escape". All they need is an air ticket, nobody is stopping them.