Hidden Facts Could Slow the Rise of the BRICS Payment System

The members' genuine commitment to the project remains uncertain; Is the BRICS de-dollarization ambition merely Russia’s wishful thinking?

This year's annual BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, made headlines with Putin’s call for the expanding club of emerging economies to create an alternative cross-border payments framework that could rival the Western-led payment system and diminish the greenback’s global dominance.

Known as BRICS Bridge, the initiative comes amid growing de-dollarization rhetoric, especially after financial message system SWIFT’s ban on Russian banks - and it appears compelling enough to unite the bloc in promoting national currencies and resisting asset weaponization.

However, a concurrent SWIFT banking conference in Beijing highlighted the complexities of implementing the BRICS payment system and advancing de-dollarization.

The four-day Sibos, which kicked off on Oct.21, attracted over 10,000 financial professionals and more than 125 exhibitors worldwide. This is the first time in its 44-year history that it has been held on the Chinese mainland.

Addressing the event, Lu Lei, deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China, reiterated the country’s commitment to financial opening up and encouraged the use of Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) - China’s worldwide payment system launched in 2015 aims to internationalize renminbi (RMB), the country’s national currency.

What’s particularly noteworthy is that China’s CIPS is actually partnering with SWIFT and utilizes its messaging service to facilitate international payments. Some misleading reports suggest that CIPS is China’s equivalent to SWIFT, but this isn't accurate. SWIFT acts like a “postman”, transmitting information between banks before funds are settled. In contrast, CIPS handles RMB clearing and settlement based on received instructions. Although CIPS has its own messaging system, it still most of the time uses SWIFT-enabled messaging as it remains smaller in scale.

Just as Alain Raes, former chief executive of Asia Pacific & EMEA at SWIFT, succinctly stated in a 2019 interview: “We see CIPS as a strategic partner.” This “strategic” partnership adds ambiguity to BRICS's efforts for closer economic and financial integration aimed at challenging the West.

Meanwhile, China’s offshore financial center reveals the long journey ahead in de-dollarization: the currency of Hong Kong - China’s offshore financial hub and entrepot - is pegged to the greenback within a tight range of HK$7.75 to HK$7.85 per US dollar under the 41-year-old Linked Exchange Rate System.

This currency anchor is part of China’s unique economic landscape. According to the impossible trinity in economics, an economy can only maintain two of the following:

independent monetary policy;

a fixed exchange rate;

free capital flow.

The Chinese mainland strives to reconcile the "impossible trinity" with strict capital controls, while Hong Kong opts for the latter two.

The distinctions help China avoid larger-scale capital outflows and at the same time provide a gateway to connect with the world. This means that China may need first to figure out a destination for its offshore financial center’s currency amid de-dollarization as it can’t afford to lose this flexibility.

The ideal option is to peg the Hong Kong dollar with RMB, but this would require China to lift capital controls, making its currency a reliable global medium of exchange and store of value.

RMB’s weight is steadily growing: Data from SWIFT showed that the RMB was the fourth-largest international trade currency in July, accounting for 4.74% of global transactions. However, this is still far behind the US dollar at 47.8% and the euro at 22.5%.

Additionally, it's not yet the right time to remove capital controls, especially as China is facing pressing issues like a real estate slump and an aging population. A key concern is that even gradual moves toward yuan convertibility could trigger significant speculative capital flows, leading to unwanted financial volatility.

One should also not lose sight of the fact that the proliferation of national payment systems challenges the necessity for a BRICS alternative to SWIFT.

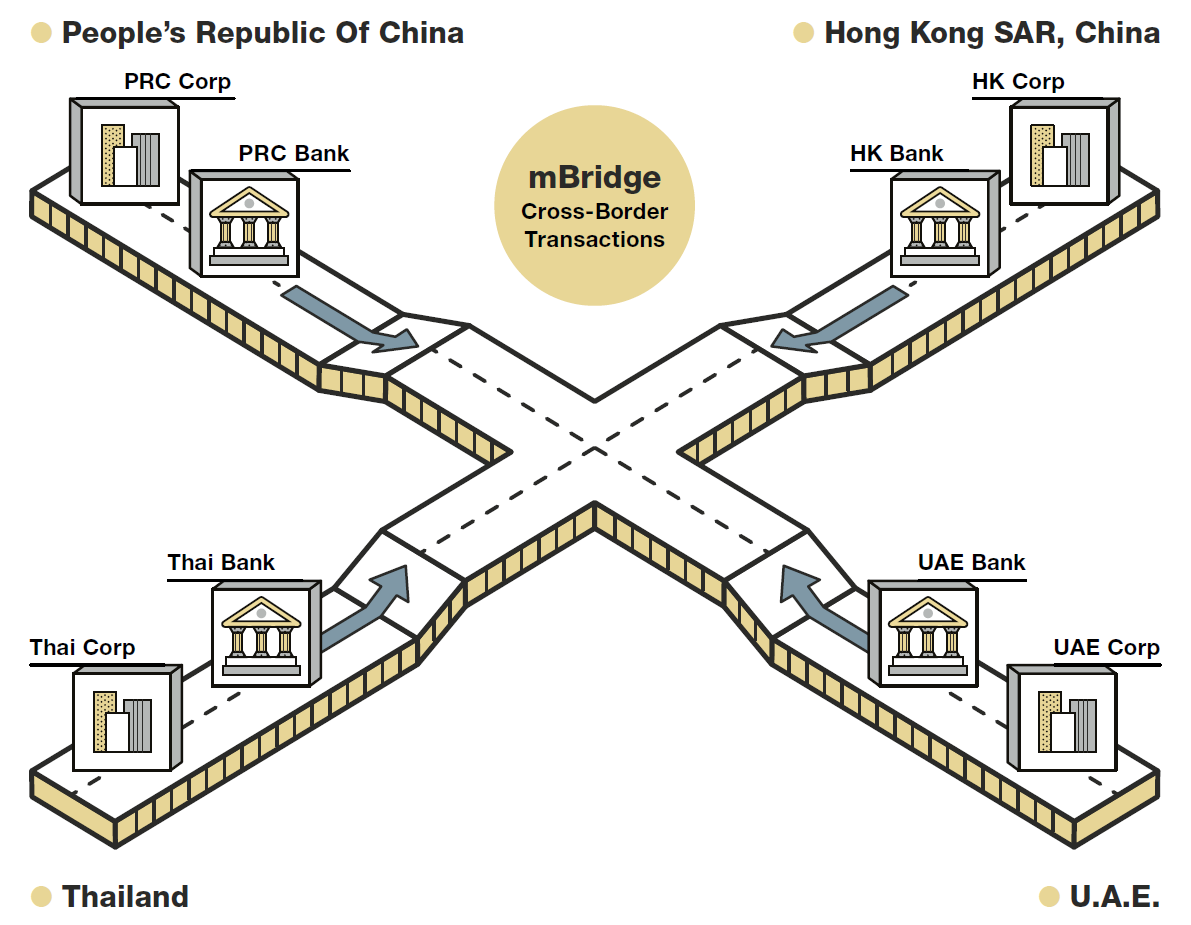

Alongside CIPS, China is developing a cross-border central bank digital currency (CBDC) project called mBridge, in collaboration with the central banks of Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Hong Kong. Unlike CIPS, mBridge creates direct digital links between participating central banks. It reached the "minimum viable product" (MVP) stage this year, making it ready for real-world testing. Members claim it can make transactions faster, cheaper, and more secure.

For sure, the BRICS Bridge is expected to build on the advancements of Bridge.

Innovative payment solutions have also taken place in India, another BRICS founding member, with its Unified Payments Interface (UPI) recording 100 billion digital transactions last year. Data from consulting firm PwC show that UPI accounts for over 80% of India’s retail digital payments and is expected to contribute to 91% by 2028-29.

More importantly, UPI is expanding globally: It is already connected to payment systems in the UAE, Singapore, Malaysia, France, and more.

With so many national payment networks sprung up, it's reasonable to question the need for a new BRICS system when countries have already developed their own.

This situation is reminiscent of John Connally, Nixon's treasury secretary, who famously told European finance ministers in the 1970s,

“The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

While the idea of subverting today’s US dollar-dominant financial system is appealing, the traditional architecture is expected to prevail for a considerable period, coexisting with emerging payment systems. Among these innovations, the BRICS payment initiative has a long way to go.

Liu Yifan raises a very important question. How can China support de-dollarization while the currency of Hong Kong - China’s offshore financial hub and entrepot - is pegged to the US dollar? I live in Hong Kong and remember that in colonial times the city was described as “a borrowed place living on borrowed time.” After its return to the motherland in 1997 HK is no longer a borrowed place, but the sense of living on borrowed time hasn't completely disappeared, people are still anxious about the fate of its currency. We try to hedge the risk with dual currency deposits and savings, in yuan and HK dollars, but we fear that is not a long-term solution. As i applaude efforts to reduce the use of the US dollar in international trade, i wonder what the impact on the HK dollar is going to be. And i am not the only one. As to the rise of alternative payment systems to bypass Western sanctions, they are still unavailable to the general public. When I travel to Russia i can't use my Union Pay card because it is issued by a HK bank that abides by the sanctions. It's a negligible problem because i am not a big spender and cash is accepted everywhere i go, but it might be a deterrent for some people. Those who are doing business with Russia face bigger obstacles when it comes to making and receiving payments. However, these obstacles are not insurmountable, Russian-Hong Kong trade is steadily growing.

Well written and interesting!

But, in my opinions: 1) the supposed trilemma is questionable, one reason it actually about trade-offs, not absolute exclusions. While a full full blast of all three might create unsustainable tensions, in practice, in some ways or others, all three, or maybe even any, are probably not fully there anyways and partial measures or compromises allow for varying degrees of each. For example, countries can adopt managed exchange rate regimes (like crawling pegs or currency bands) that offer stability without being full fixed. Also, capital flow management, such as forms of capital controls, capital inhibitors, or macroprudential regulations, permit partial openness without sacrificing all monetary policy autonomy. Amongst other things.

And more importantly, 2) in my view the biggest threat to King Dollar is the same biggest threat to the highly globally extractive planetary financial-economic system in general: a wave of sudden -- not necessarily violent -- true and real political change in the so called developing nations