Damascus steel: Syria's fragments are being divided among its neighbors

Damascus steel is legendary for its strength, but a hard enough strike to a weak spot makes it shatter. The swift collapse of Republican Syria in less than two weeks is a dark confirmation of this.

After the fall of Aleppo and the voluntary abandonment of Hama by government forces, the flywheel of the conflict began to rapidly accelerate. Even the most optimistic experts did not give the Republic more than a couple of months to live – although they hoped that the “march of the armed opposition,” the backbone of which was made up of militants of varying degrees of radicalism, could be stopped on the approaches to the capital; by diplomatic or military means.

However, a few days later Damascus also fell: the Syrian government surrendered to the mercy of the victors, and President Bashar al-Assad left the country.

The fragments of the republican authorities are talking about a peaceful transfer of power and holding fair elections. They are echoed by yesterday's radicals, promising to harshly suppress terrorist and criminal activity in the territories of the "new Syria", and also promising the Syrian people a way out of the protracted crisis. However, as the history of other Arab countries, Libya and Iraq, shows, the triumph of the armed opposition very quickly turns into a struggle for power between former allies. Despite the fact that the opposition is trying to present a united front and not to publicly flaunt disagreements within its ranks, it is becoming increasingly difficult to hide dissatisfaction with them.

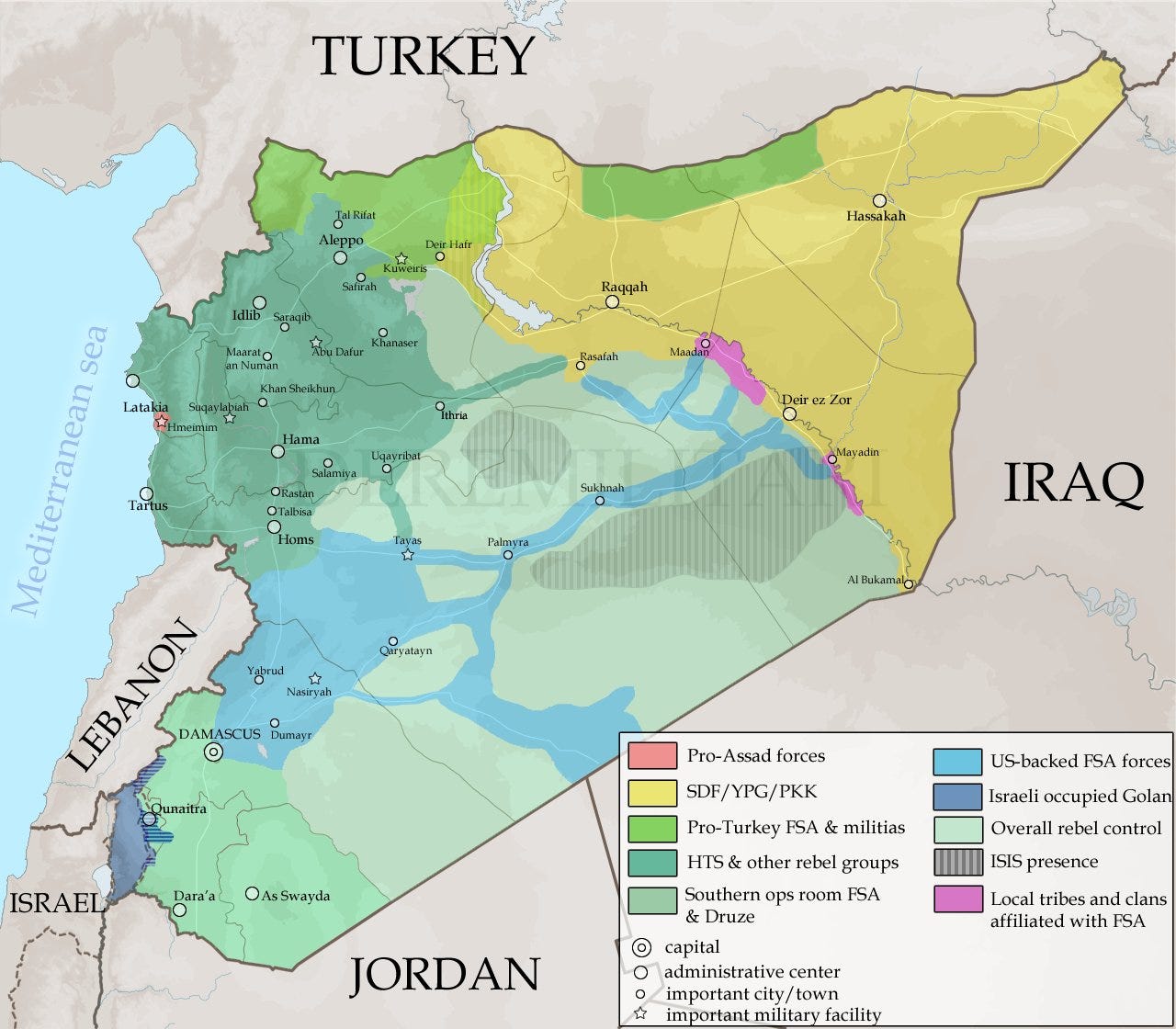

It is obvious that the leadership of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leader Muhammad al-Julani, who is tipped to be the new ruler of “democratic Syria,” does not suit everyone. The “progressive jihadist,” as al-Julani has been dubbed by the Western press, has still not been forgiven for his intrigues behind the backs of Ankara and Washington, as well as his repressions against political opponents in Idlib. Discontent with the privileged position of HTS has not gone away either – although other media opposition commanders also participated in Operation Dawn of Freedom against Assad.

In addition, al-Julani has a clear “terrorist aura.” He once went through the Al-Qaeda school, fought against government forces on the side of ISIS, and still has a bounty on his head from the US government. And although it is a matter of time before his reputation is cleared, the hypothetical transfer of power to the head of HTS still looks dubious.

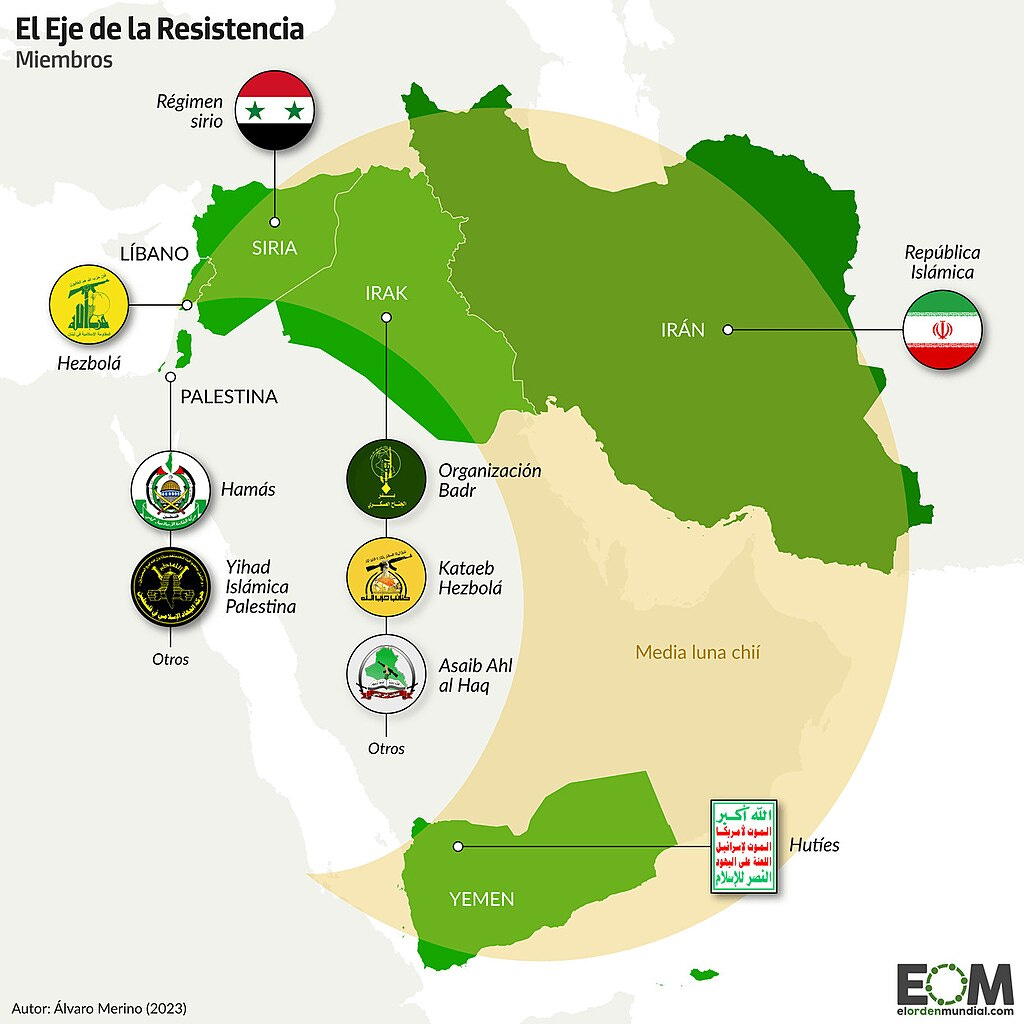

It should be noted that the end of the Assad dynasty in Syria significantly changed the balance of power in the Middle East. Of course, Syria's influence on the international arena (compared to the era of Assad Sr.) was not as great, but the country occupied an important place in the Middle East security system.

Russia and Iran, key allies of the Republican Damascus, although they failed to tip the scales in favor of the Syrian government, tried to maintain the status quo until the very end and ultimately fulfilled their partnership obligations in full.

And if Moscow initially took a “supportive” position in the conflict, focusing not so much on force as on diplomatic instruments, then official Damascus clearly expected much more help from Tehran, up to and including sending an expeditionary force to help the retreating Syrian army.

Recent leaks from the Syrian cabinet also indicate that Damascus was serious. According to some sources, up to half of the Syrian government signed the call to the Iranian authorities to assist. The stakes of the "Persian party" were quite clear - in 2020, the Middle East already saw the effectiveness of external intervention - when the Turkish expeditionary force in Libya stopped the "victorious march" of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar on Tripoli. In addition, Tehran, like Moscow, was surrounded by the "aura of victory" after the successful defeat of the "terrorist caliphate" in Syria.

However, the Iranians did not come. Nor did the groups that were part of the "Axis of Resistance" provide any assistance. The Hezbollah units and pro-Iranian militias (up to 5,000 people in total) operating on Syrian territory did not engage in serious combat with the armed opposition.

This has drawn the ire of pro-government media: bloggers and journalists have vied with each other to claim that Iran has “sold” Syria to its enemies in exchange for hypothetical sanctions relief and saving the remnants of Hezbollah from destruction. In response, the Iranian Fars news agency, the official mouthpiece of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), released a long article explaining the actions of official Tehran. The Persians placed responsibility for the Syrian collapse on the Syrian top leadership. Allegedly, Assad, dissatisfied with the excessive influence of Iranian advisers on his country's policy, preferred in times of crisis to trust the guarantees of "Arab friends" (meaning Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE), but they preferred to limit themselves to demonstrating concern.

The scathing wording addressed to the former ally is quite understandable: with the fall of the Assad regime, Tehran lost the ability to act openly in Syria, as well as to ensure the rapid transfer of pro-Iranian forces from Iraq to Lebanon through Syrian territory. Given the general instability of the ceasefire in southern Lebanon, such a situation is causing concern among the Iranian leadership. In this context, the urgent dispatch of Iranian General Javad Ghaffari (who received the telling nickname "Butcher of Aleppo") to Syria in the first days of the crisis looks, in the context of current events, like a behind-the-scenes coordinated operation to withdraw combat-ready units. On the other hand, Iranian military advisers remained in Damascus until the very end, ensuring the exchange of information between the IRGC and the Syrian army.

Turkey reacted much more positively to the fall of the Assad regime, using proxy forces to de facto dismantle the republican government. After taking Damascus, the armed opposition turned some of its forces toward Syrian Kurdistan and occupied Manbij, pushing the Kurdish forces to the other side of the Euphrates. Turkey's ultimate goal is to weaken and divide the Syrian Kurds as much as possible, if not to destroy them, and to demonstrate the "inevitability of punishment" for Ankara's enemies. True, the movement here is much slower - the Kurds regularly counterattack, and in Manbij itself, there are still pockets of resistance.

It is noteworthy that the United States, a strategic ally of the Syrian Kurds, has not yet intervened in the confrontation. On the other hand, if pro-Turkish forces approach Syria's oil-bearing regions, Washington may well go for a "flag show" to cool the ardor of its partners. Especially since the armed opposition has not responded in any way to the White House's statements about maintaining its military presence in the country.

Israel was the most active. When it became clear that the Syrian troops had completely lost their combat capability, the IDF struck from the Golan Heights and began a rapid advance into Syrian territory. The Netanyahu government unilaterally declared the demarcation line established after the Yom Kippur War (1973) invalid and occupied parts of the provinces of Daraa, As-Suwayda, and El-Quneitra. And if in the case of Daraa the IDF's attack could be explained by the terrorist threat - in light of yet another riot of jihadists who had escaped from prison - then in other areas Israel acted proactively, simultaneously bombing border garrisons occupied by anti-government forces.

Moreover, Israel has made it clear to the new Syrian authorities – who, by the way, have publicly demonstrated a willingness to engage in dialogue with the Israelis on détente – that the airstrikes are not “excesses on the ground”; the IDF will continue to bomb Syrian airfields and cities, including the capital, “for reasons of national security.”

It is not to be ruled out that Tel Aviv will not stop there and will try to consolidate its success by forming a puppet state of local (for example, Druze) elites in the occupied territories. Especially since many Israeli politicians – including, for example, Foreign Minister Gideon Saar – have previously repeatedly suggested that Netanyahu create his own version of the “Axis of Resistance” based on the Kurdish and Druze communities.

It is too early to draw far-reaching conclusions about the further development of the situation in Syria. Many issues – including the prospect of the continued presence of Russian military bases in the country – remain in limbo. The armed opposition led by al-Julani showers Russia with exhortations, promising to ensure “observance of interests” and equal cooperation. True, no one can say how strong these promises will be when the new government gets on its feet.

Coastal bases are a “tasty morsel” for which other participants in the Syrian conflict would not mind fighting – Turkey itself would clearly not mind having another “transit point” on the way to Africa.

And Ankara will clearly have more tools to influence the government, which was raised from yesterday’s “Idlib managers.”

About the author:

Dr. Leonid Tsukanov, a PIR Center Consultant and RIAC expert, is an international journalist recognized for his achievements in international affairs. He was nominated for the Nasser Bin Hamad International Youth Creativity Award (Science, 2021), was a quarterfinalist for the Innovators in Global Affairs Award (International Cooperation, 2021), and received the G.M. Evstafiev Award for young professionals in international security and nuclear non-proliferation (2022). He has completed advanced training in Middle East regional security, cybersecurity, and terrorism studies at institutions including Tel Aviv University, MGIMO University, and Universiteit Leiden.

Syria’s Collapse: Chaos or Strategy?

Syria’s sudden regime change in just 10 days has ignited intense global debates. Was this a chaotic downfall or a calculated geopolitical maneuver? In our latest video, we analyze the crisis from a fresh perspective, exploring whether the fall of the Assad regime is tied to a broader strategic plan by the BRICS nations.

Drawing on the insights of

, a renowned market analyst, we investigate how Syria’s collapse might signal a power shift in the Middle East. Could this event reflect a deliberate move by Russia, Iran, and their allies to challenge Western dominance? The sudden rise of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its offensive raises key questions—was this chaos or part of a larger geopolitical strategy?Our video dives into the links between Syria, BRICS geopolitics, and Eurasian strategies. Could this crisis become a turning point for global power dynamics in 2024? By re-evaluating the Syrian collapse through a new lens, we challenge conventional views and uncover potential hidden strategies.

Don’t miss this deep dive into the forces reshaping Syria and the global order. Watch now to explore the pivotal connections and implications of this crisis!

Things are moving. If we think in long-term, we can see three things:

1.- The Otoman Empire (the main player in the region for centuries) will return. It has his own history, a nuclear ethnic group (extended in all Eurasia), a geographical position that is a luxury and it is on his revival phase, after the desintegration happened at the end of XIX century and beggining of the XX.

2.- Islam it is the core of social cohesion fort this societies. They do not accept political power, but they accept religious one. They see political power as belongint to the elits, but they see Islam as "we, the people". Islam is analogous to democracy (at least in a functional way), because give to people a feeling of identity shared, a notion of representation for their really interest. The changes are comparable to the emerging of Nation-States in the West during the last two centuries.

Islam is a universalist religion, and that gives a power that history prove us is very important (an excess, of course, could be it grave, but it is on a growing cycle). That's why it is so strong (the same apllies to Israel and the jewish religion) and, that is my bet, when they get really modernize (and this also is connected with Turkey), they could expand to all Central Asia and shock with Russians, the Chinese and the Indians. And I have to say that most sociologist and political analyst undermine the importance of social cohesion and religion.

My only doubt it is on the development of Islam to the East, and how will be structured with other countries and how will behave Pakistan or the more "oriental muslims".

3.- The issue will be focus on the "fight" between islamic factions. There is an oposition between chiism and sunnism that, by the moment, focus different States with different interests. After that, the oposition could change to the Jews (for me, Israel has win a battle, but will lose the big war inevitably: it will not exist in a century). We don't know the exact number of Islamic States, and how will be the competition between Turkish and Wahabies. However, we can talk without any doubt about the emerging of Islamic potencies, and their importance on the future. We also don't know how things will evolve in Magreb, because this countries are "softer" and their location on Africa make them a bit different.

Of course, there is always the chance that internal struggle make them weak in relation to other actors, but seen the weakness of Russia and Europe, I think that will be consolidated. Will be later how they relation with India and China.

The addition of Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the prospective membership of Saudi Arabia to BRICS highlights just how challenging it is for the group to act as a unified force, particularly in the Middle East. These countries have deeply rooted rivalries and conflicting priorities that make collaboration difficult. For example, Saudi Arabia and Iran have been on opposite sides of regional conflicts for years, and their inclusion in the same bloc doesn’t change their fundamental distrust of each other. Egypt, while often aligned with Saudi Arabia on some issues, has its own ambitions and clashes directly with Ethiopia over the Nile River dispute and the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Ethiopia, in turn, is focused on its own development goals, which often put it at odds with its Arab neighbors.

Beyond these regional tensions, BRICS as a whole struggles to align on Middle Eastern issues. Russia and China, the group’s dominant players, have very different approaches: Russia leans on military partnerships, as seen in its involvement in Syria, while China focuses on economic investments and trade. Meanwhile, countries like Brazil and South Africa are largely disengaged from Middle Eastern geopolitics, concentrating instead on their own domestic and regional priorities. This lack of shared focus makes it hard for BRICS to present a united front.

At its core, BRICS isn’t a unified geopolitical bloc but more of a platform for dialogue among nations with very different agendas. In a region as complex and fractured as the Middle East, this lack of unity becomes even more apparent, making it nearly impossible for the group to take a cohesive approach to the region’s challenges.