Should Türkiye Join BRICS? What the Numbers Tell Us About a Complex Choice

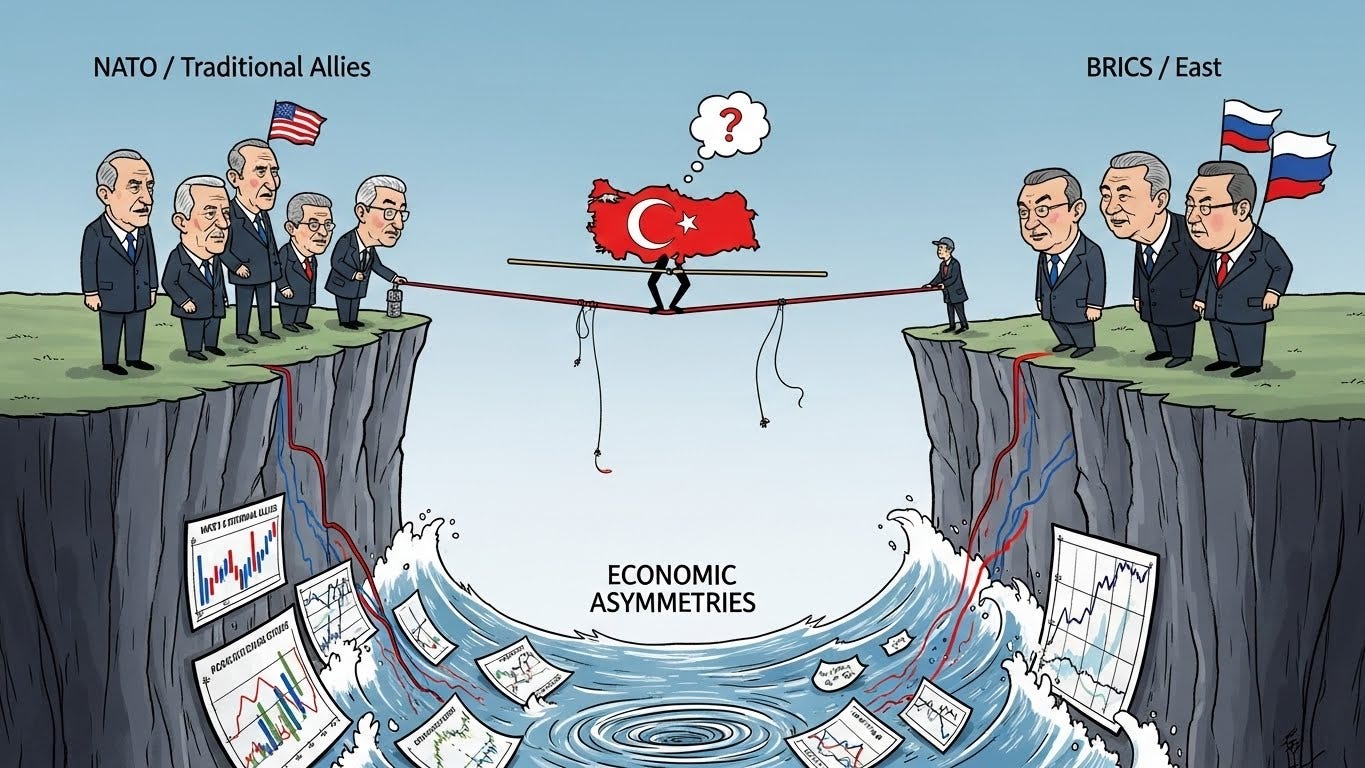

Turkey's BRICS bid tests whether a NATO member can bridge East and West—or if this gamble will isolate Ankara from allies while deepening dependencies on China and Russia.

Would joining BRICS position Türkiye as a powerful bridge between civilizations—or isolate it from its traditional Western allies? As Ankara pursues “partner status” with the emerging economies bloc, the answer reveals itself in layers of economic calculation, geopolitical ambition, and institutional performance.

Türkiye stands at a pivotal geopolitical moment. In November 2024, the Turkish Trade Minister Ömer Bolat confirmed that the BRICS group—originally comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, recently expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—has offered Türkiye “partner country” status. This offer falls short of the full membership Ankara initially sought when President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan attended the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, in 2024, yet it represents a significant step for a nation that has been a NATO member since 1952.

Understanding what “partner status” means is crucial. Unlike full membership, which would give Türkiye voting rights and complete integration into BRICS institutions like the New Development Bank, partner status serves as a transitional category—a waiting room of sorts—allowing Türkiye to engage with the bloc without full commitment. This distinction matters because it reflects BRICS’ own uncertainty about admitting a NATO member, and Türkiye’s hesitation to fully pivot away from the West.

The Economic Imperative: Following the Money

The economic case for Türkiye’s BRICS engagement appears compelling on the surface. In 2023, nearly 60% of Türkiye’s total trade occurred with BRICS countries, surpassing its commerce with the European Union, its largest traditional trade partner. Türkiye imports heavily from Russia and China, which together account for 87% of its BRICS-related trade. Yet herein lies the first cautionary note: these relationships are highly asymmetric, with Turkish exports to these countries representing only 15.7% of its imports.

The economic logic becomes clearer when examined through the lens of recent research. A comprehensive study published in the Journal of Emerging Economies and Policy assessed BRICS countries—including Türkiye as a prospective member (designated as “BRICS-T”)—across eight critical dimensions: voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption, economic freedom, and human development. Using sophisticated multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods, the study ranked countries from 2018 to 2022 and found that Türkiye consistently placed sixth among the ten nations examined.

This mid-tier performance reveals both opportunity and vulnerability. Türkiye scored relatively well on human development and economic freedom indices but performed poorly in areas such as control of corruption and regulatory quality. The United Arab Emirates dominated all rankings, followed by South Africa and India, while Russia, Ethiopia, and Iran occupied the bottom positions. For Türkiye, joining BRICS could mean aligning with a mixed bag—partnering with economic powerhouses like the UAE and India, but also with structurally challenged economies like Iran and Ethiopia.

Would BRICS membership improve Türkiye’s economic trajectory? The research suggests that human development, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability emerged as the most critical factors influencing national performance within the bloc. Türkiye’s weaknesses in corruption control and governance effectiveness could actually be exacerbated within a group where such challenges are common among several members.

Geopolitical Positioning: The NATO Elephant in the Room

Türkiye’s NATO membership casts a long shadow over its BRICS ambitions. No other NATO member has sought to join BRICS, making Türkiye’s bid unprecedented and symbolically charged. Erdoğan has insisted that BRICS membership would complement rather than replace Türkiye’s Western alliances, describing it as an opportunity for enhanced economic cooperation rather than a geopolitical realignment. Turkish officials have repeatedly stated that potential BRICS participation would not affect Türkiye’s NATO responsibilities.

Yet such reassurances strain credulity. BRICS has increasingly positioned itself as a counterweight to Western-dominated institutions like the G7, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. The bloc’s 2024 expansion, which brought its share of global GDP to approximately 36% and its population representation to 47%, signals an explicit challenge to the post-World War II international order. China and Russia, BRICS’ dominant powers, have framed the organization as a vehicle for multipolarity—a diplomatic term for reducing American hegemony.

Türkiye’s calculus here reflects deeper frustrations. After decades of stalled EU accession talks and perceived marginalization within NATO—particularly regarding defense procurement and regional security issues—Ankara has grown increasingly disillusioned with Western institutions. The BRICS bid represents what analysts call a “strategic hedge,” allowing Türkiye to leverage its position between East and West. As independent consultant Arın Tunca notes, “Any new BRICS member is clearly keen to leverage the enhanced solidarity of emerging economies to diminish reliance on developed nations, particularly the United States”.

But would this hedging strategy deliver the autonomy Türkiye seeks, or merely create new dependencies? The research on BRICS-T countries reveals instructive patterns. Political stability emerged as foundational for economic growth and human development within the bloc, while institutional quality—including governance frameworks and regulatory effectiveness—significantly influenced investment patterns and economic resilience. Türkiye’s bid to balance between rival power centers could undermine the very political stability that enables economic progress, particularly if it generates suspicion and distrust among both Western and BRICS partners.

The Infrastructure Question: Access to Alternative Finance

One tangible benefit Türkiye anticipates from BRICS membership is access to the New Development Bank (NDB), established in 2014 to finance infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging economies. Türkiye imports approximately 92% of its energy and has significant infrastructure needs. The NDB and South-South investment flows, particularly from China, could theoretically reduce Türkiye’s dependence on Western financing and provide capital for ports, railways, and energy grids.

China has already demonstrated interest in Turkish infrastructure, with the electric vehicle manufacturer BYD announcing plans to invest $1 billion in a new plant in Türkiye following Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan’s recent visit to Beijing—the first by a high-level Turkish diplomat in 12 years. Türkiye also positions itself as a potential trade conduit between the EU and Asia, a role that BRICS membership might enhance.

Yet the research findings inject skepticism into this rosy scenario. The study identified economic freedom as among the least important criteria influencing BRICS country performance, with human development, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability emerging as far more consequential. This suggests that merely accessing alternative financing won’t transform Türkiye’s economic prospects if underlying governance challenges remain unaddressed. Moreover, the highly asymmetric nature of Türkiye’s trade with China and Russia—importing far more than it exports—could deepen rather than diversify economic vulnerabilities.

Regional Leadership or Global Isolation?

Proponents argue that BRICS membership could amplify Türkiye’s regional leadership in the Middle East and Central Asia. The research notes that Türkiye has emerged as a serious economic player in Africa and Central Asia, and BRICS could provide a platform for shaping global economic policies while asserting regional power. Membership might enhance Türkiye’s ability to mediate conflicts, promote economic integration, and advocate for Muslim-majority countries within the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Critics counter that Türkiye’s BRICS bid could alienate Western partners at precisely the moment when Türkiye needs them most. The EU remains Türkiye’s largest trade partner, and NATO provides security guarantees that no BRICS alternative can replicate. The research revealed that countries with higher governance scores—particularly in control of corruption, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality—achieved better human development outcomes. Rather than shopping for new institutional homes, Türkiye might benefit more from addressing the governance deficits that keep it in the middle tier of national performance.

The question of whether BRICS membership would enhance or undermine Türkiye’s global influence hinges on a paradox: the same assertive foreign policy that drives Türkiye toward BRICS also generates “suspicion and distrust” that could undermine its aspirations. Türkiye’s recent actions—from opting out of Russia sanctions to cultivating relationships with US adversaries like China and Iran—have already strained Western relationships. Full BRICS membership might provide Türkiye with new partners, but at the cost of old allies.

The Verdict: A Strategic Gamble with Uncertain Payoffs

So would Türkiye’s entry into BRICS be beneficial or detrimental? The research evidence and geopolitical analysis suggest an answer more complex than simple benefit or harm: it depends entirely on what Türkiye hopes to achieve and what it’s willing to risk.

If Türkiye’s goal is economic diversification and reduced dependence on Western institutions, the research findings offer lukewarm support at best. Türkiye’s mid-tier performance in governance indicators—particularly its weaknesses in corruption control and regulatory quality—suggests that joining a bloc where such challenges are widespread among members might reinforce rather than remedy these problems. The economic asymmetries in Türkiye’s relationships with China and Russia could deepen rather than diminish.

If Türkiye seeks enhanced geopolitical autonomy and regional leadership, BRICS membership might deliver symbolic gains but at considerable cost. The “partner status” currently on offer provides engagement without full commitment—perhaps the worst of both worlds, generating Western suspicion without delivering Eastern benefits. Full membership would intensify these tensions, potentially isolating Türkiye from NATO and the EU without providing equivalent security or economic guarantees from BRICS.

The research makes clear that political stability, institutional quality, and governance effectiveness matter far more than organizational affiliations in determining national development outcomes. Türkiye’s consistent sixth-place ranking among BRICS-T countries from 2018 to 2022 suggests that the fundamental challenges Türkiye faces—corruption, regulatory inefficiency, governance deficits—won’t disappear simply by changing alliance structures.

Perhaps the most revealing insight comes from the research methodology itself: when evaluating national performance across multiple criteria using objective weighting methods, human development, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability emerged as most critical, while economic freedom and institutional affiliations proved far less consequential. This suggests that Türkiye’s BRICS bid, however symbolically important, addresses secondary rather than primary determinants of national success.

The question, then, is not whether Türkiye’s BRICS membership would be good or bad, but whether it represents a strategic gamble that Türkiye can afford—and what the country might accomplish if it invested the same political capital in addressing the governance challenges that keep it perpetually in the middle tier of emerging economies, regardless of which organizational acronym appears on its membership card.

A Critical Caveat: What the Research Cannot Tell Us

Yet before drawing firm conclusions from this analysis, a crucial methodological limitation demands acknowledgment: the research examining BRICS-T countries covers the period from 2018 to 2022, years when the recent expansion members, including Türkiye, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, were not part of the bloc. The study, therefore, measures these countries’ performance in isolation, not the potential synergies or transformations that BRICS cooperation might catalyze.

This temporal mismatch matters profoundly. The entire premise of Türkiye’s BRICS interest rests on the assumption that membership would unlock new economic opportunities, provide access to alternative financial systems through institutions like the New Development Bank, and create trade efficiencies through enhanced South-South cooperation. None of these dynamics appear in the 2018-2022 data because they simply didn’t exist for the prospective members during that period.

The research reveals that Türkiye ranked sixth among ten BRICS-T countries during this timeframe, performing below the UAE, South Africa, and India but above Russia, Ethiopia, and Iran. But this ranking reflects each country’s standalone performance across governance, development, and economic freedom indicators—not how Türkiye might perform within an integrated BRICS framework with enhanced trade relationships, coordinated policy initiatives, and shared institutional resources.

Consider what the data cannot measure: Would access to the New Development Bank meaningfully improve Türkiye’s infrastructure development? Would deeper integration with BRICS economies help Türkiye address its massive trade imbalances with China and Russia, or merely entrench them? Would the “enhanced solidarity of emerging economies” that Türkiye seeks actually materialize in concrete benefits, or prove more rhetorical than real? Would collaboration with high-performing members like the UAE and India elevate Türkiye’s governance standards, or would alignment with struggling economies like Iran and Ethiopia drag performance downward?

The research methodology—employing sophisticated multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques to assess political stability, human development, and economic freedom—provides robust insights into each country’s baseline institutional capacity. These baseline measures matter enormously, as the study demonstrates that governance quality, regulatory effectiveness, and human development infrastructure serve as fundamental determinants of national success. But they cannot capture the dynamic effects of membership itself.

This limitation cuts both ways. Optimists might argue that the research underestimates BRICS’ potential benefits because it doesn’t account for the cooperation effects that full membership would trigger. Türkiye’s mid-tier performance might improve substantially through knowledge transfer from high-performing members, preferential trade arrangements, or coordinated diplomatic initiatives. Skeptics, however, could counter that the research actually overestimates the likely benefits, since organizations often underperform the aggregate capacity of their individual members due to coordination challenges, conflicting interests, and bureaucratic inertia.

The expanded BRICS now represents 36% of global GDP and 47% of the world’s population. Yet this statistical heft doesn’t automatically translate into institutional effectiveness or member benefits. The bloc includes both the dynamic UAE, which topped all research rankings, and struggling economies like Ethiopia and Iran, which placed at the bottom. Whether Türkiye would rise toward the UAE’s trajectory or sink toward Russia and Iran’s patterns remains fundamentally unknowable from pre-membership data.

The Question That Remains

So would Türkiye’s entry into BRICS be beneficial or detrimental? The research evidence and geopolitical analysis suggest an answer more complex than simple benefit or harm: it depends entirely on what Türkiye hopes to achieve, what it’s willing to risk, and—crucially—how BRICS membership might transform the very governance and economic indicators that currently place Türkiye squarely in the middle tier of emerging economies.

The data from 2018 to 2022 tells us where Türkiye stands today: sixth among BRICS-T countries, with relative strengths in human development but persistent weaknesses in corruption control, regulatory quality, and governance effectiveness. What the data cannot tell us is whether BRICS membership represents the catalyst that elevates Türkiye’s performance or merely a new organizational label attached to unchanged institutional realities.

Perhaps the most honest assessment is this: Türkiye’s BRICS gamble represents a bet on cooperation effects that existing data cannot measure, undertaken at a moment when the country’s governance fundamentals suggest such bets carry substantial risk. The research makes clear that political stability, institutional quality, and human development matter far more than organizational affiliations in determining national success. Whether BRICS membership enhances or undermines these foundational elements won’t become clear until years after Türkiye joins—at which point the gamble will have already been made, and reversing course may no longer be possible.

The question isn’t just whether Türkiye should join BRICS. It’s whether Türkiye can afford to make a major geopolitical bet whose potential benefits remain unmeasured—and perhaps unmeasurable—by the very research that best illuminates the starting conditions from which that bet would be made.

Join the Conversation:

📌 Subscribe to Think BRICS for weekly geopolitical video analysis beyond Western narratives.